Five Plants You Should Learn to Identify This Winter

Prefer to listen to this article? No problem! Four Season Foraging now offers free audio versions of articles with the help of a text-to-speech website. Simply click the play button on the right!

Five Plants You Should Learn to Identify This Winter

Identifying plants is typically easiest when the flowers are blooming, but with practice, you can identify plants any time of year—even in the winter! Truth be told, I really enjoy winter plant identification, and think there are lots of good reasons to start doing it. For starters, it’s a fun activity that helps you get outside during this chilly season. It’s also important to the practice of foraging: both for finding winter plants to forage and to locate plants that you can return to later in the year, when they’re ready to pick.

The plants listed below are common in eastern North America, are easy to identify, and are great wild edibles. If you don’t have much experience with winter plant ID, I think these are great species to start with. If you already practice identifying plants in the winter, you’re likely familiar with these species, but a refresher never hurts!

I list resources particular to each plant below, but here are some general recommendations that will help you with winter plant ID as well as the overall practice of identifying plants:

Regularly visit the same plants throughout the year to see what they look like at different stages of growth.

Get into the habit of drawing and journaling about plants. You don’t have to be a brilliant artist to do so! Just the practice will help you pay closer attention to detail and remember key identification features.

For winter plant ID, pay special attention to bark, winter buds, seeds, dead stems, and/or the general shape of plant. The exact features to look out for will depend on the species.

And now for the stars of the show, the plants themselves!

Curly Dock (Rumex crispus)

The seed head of curly dock.

This common plant is a versatile wild food with several edible parts. The tender green growth of leaves and stems are delicious in spring and summer. The root can also be harvested for medicinal purposes in early spring and late fall, though it is typically thought to be too bitter for general consumption. However, probably the most conspicuous and voluminous edible portion is the seeds, which mature in fall and often hang on the plant late into the winter.

I recommend learning to identify curly dock in the winter not just for its tasty seeds, but also so that you can mark their locations and return to them when other portions are prime for picking. Probably the best way to do this is to become familiar with the seeds themselves.

A curly dock seedhead in the winter.

The seeds are borne on upright stalks that grow to 1 to 5 feet in height, usually around 3 feet. Each seed is wrapped in a three-sided, reddish brown, papery sheath, and is only 2 to 3 mm long on its own (about 6 mm including the sheath.) There are many Rumex species that grow in Minnesota, but careful inspection of the seeds will tell you if it’s curly dock or not. First of all, the stalks that hold the seeds have swollen joints about 1/3 of the way down the stalk. Next, when examining the papery sheath, note the oval capsule that extends about half the way down the sheath. (This looks a bit like a seed, but it is a non-reproductive structure.) When removed from its papery wrapping, the seed itself is three-sided. The paper wrapping is oval or heart-shaped and has a slightly ragged edge. (See Minnesota Wildflowers for an enlightening side-by-side comparison of different Rumex seeds.)

Curly dock leaves emerging in spring.

If squinting at seeds isn’t your cup of tea, don’t fret! In the spring curly dock sends up long, narrow leaves, which typically become strongly curly along the edge as they age. These aid in identification. However, if all else fails, you could just taste the plant! As far as I know, none of the Rumex species that grow in Minnesota are poisonous, though you may certainly come across unpalatable species.

Safety note: Curly dock contains oxalic acid, which is a compound found in several wild plants, including lamb’s quarters, yellow wood sorrel, and purslane. Oxalic acid often gets a bad rap because it blocks absorption of minerals such as calcium and iron. However, it is found in many cultivated plants, including rhubarb, spinach, and Swiss chard, but one rarely hears warnings about eating those foods. Basically, as long as you're not severely mineral deficient, and as long as you're not consuming unreasonably massive amounts of these plants, you should be fine! For more on oxalic acid, check out this fascinating and informative article.

White Pine (Pinus strobus)

A stand of white pines planted in a park. Note the wispy appearance of the leaves.

If you’re interested in eating evergreens, white pine is a good place to start! This native tree grows across eastern North America in upland forests. It’s also fairly commonly planted in yards, parks, and other tended landscapes. White pine is generally considered safe for consumption across the board. That and the fact that it’s quite easy to identify make it a good candidate for winter plant ID as well as winter foraging.

A white pine twig showing the needles in bunches of five.

For identification purposes, the main thing to remember is that white pine needles grow in bundles of five. (A useful device to help remember this is that “white” has five letters.) All pine needles grow in bunches, often in twos. This is distinct from most other Minnesota cone-bearing trees—such as firs, spruces, and eastern hemlock—whose needles grow singly from the twig. Tamarack is the notable exception, but its needles grow in clusters of 10 to 35! Furthermore, tamarack is a deciduous conifer, meaning that the needles turn brown and fall off in autumn, and return the following spring.

A white pine growing in a hardwood forest.

White pines have a unique appearance, and in time you should be able to recognize them from a distance. A healthy tree can reach towering heights of around 120 feet; in fact, they’re often so tall that their tops poke out from amongst neighboring trees. The bark of white pines becomes dark and furrowed with age. Another distinct feature is the texture of the needles; many Minnesota evergreens have stiff, rigid needles, but those of white pine are softer and have a wispy appearance from a distance. Finally, the cones of white pine are longer and narrower than those of other Minnesota pines, reaching 4 to 8 inches in length at maturity. You can check out Minnesota Wildflowers for great photos illustrating the difference between Minnesota pine needles and pine cones.

White pine needles make tasty tea, infused vinegar, and other infusions. They’re also high in vitamin C and have useful medicinal properties for the winter, helping fight colds and flu by soothing sore throats, expelling mucus in the lungs and sinuses, and helping break fevers with its diaphoretic properties. See my article about white pine vinegar for more details on harvesting and preparation.

Burdock (Arctium spp.)

The dead winter stalk of burdock.

Burdock is probably best known for its clingy burs that get stuck to just about anything that brushes by them, be it your clothing, your hair, or your dog’s fur. Believe it or not, these sticky seed heads were the inspiration for velcro! Well, they may be a bit annoying, but I’m personally glad that they exist, because they make it easy to identify the dead winter stalk of burdock! And that’s useful because it points to the location of where new plants will emerge in the spring.

A spring-time basal rosette of burdock.

There are many edible parts to burdock: the root, the leaf stalk, and the flower stalk. Of these, the root is probably the most popular. It is even cultivated in Japan and sold under the name “gobo.” The root should be dug up in early spring or late fall using a shovel (don’t attempt it with only a trowel, as it can reach depths of three feet!) Burdock is a biennial, meaning that in its first year it only sends up a basal rosette of leaves and does not flower. Once it has stored enough starch in its root, it will send up a flower stalk and go to seed, typically in its second or third year. The root should not be dug after the flower stalk appears, as the plant takes energy from the root to reproduce, leaving it woody and tough. After going to seed, the plant dies. Therefore, the dead stalks are not connected to any edible portion, but they do strongly indicate that fresh burdock plants will appear in that same location in the spring! See my article about burdock for more details on harvest and preparation.

A closer view of burdock seed heads.

Becoming familiar with burdock seed heads is therefore useful to discerning the location of burdock roots and other edible parts. Thankfully, there really isn’t anything that looks and acts like burdock burs! They should be brown, circular or oval in shape, and have many stiff bristles with hooks on the end. Size varies depending on the species, but they are usually 1/2 inch to 1 1/2 inches in diameter. And of course, they should easily stick to textured surfaces! Just don’t put them in your hair when you test that quality.

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

A hackberry tree in winter with fruit on the branches.

Hackberry is one of the few wild edibles in Minnesota that is actually better to pick in the wintertime! This is because the fruits are small (around pea size) and can be finicky to harvest in sizable quantities when the leaves are still on the tree. Luckily, hackberry fruits are dry, much like figs or dates, so they stay don’t ferment on the branch like other juicier fruits do. Hackberries ripen in late summer (mid-to-late August in the Twin Cities area), but I’ve seen them on the tree as late as May of the following spring!

A hackberry twig with leaves and fruit.

A hackberry leaf with warty protrusions called galls.

Hackberry is native to the eastern and central US, and can be found growing in moist hardwood forests, often in floodplains or near rivers. It is very easy to find in the Twin Cities, as it is often planted in yards, parks, and boulevards. Hackberry is a medium-sized tree that will grow to heights of about 60 feet.

The leaves of hackberry are alternately arranged on the stem. They have an asymmetrical heart-shaped base, and come to a sharp point at the tip. The leaves are often covered in warty protrusions called galls, which are created by insects laying their eggs. These are so prevalent that you can use them as an identification feature, though of course they’re not on every single tree or leaf.

The fruits ripen to a brownish purple color in late summer. Though they are commonly referred to as berries, they are actually stone fruits, like cherries or apricots. When eating them, it is best to crunch through the hard pit, as the proportion of pulp is small, and the nut meat inside the pit is edible and delicious. Don’t do this if you have sensitive teeth or delicate dental work, however! There are other options available, like grinding the berries or making hackberry milk.

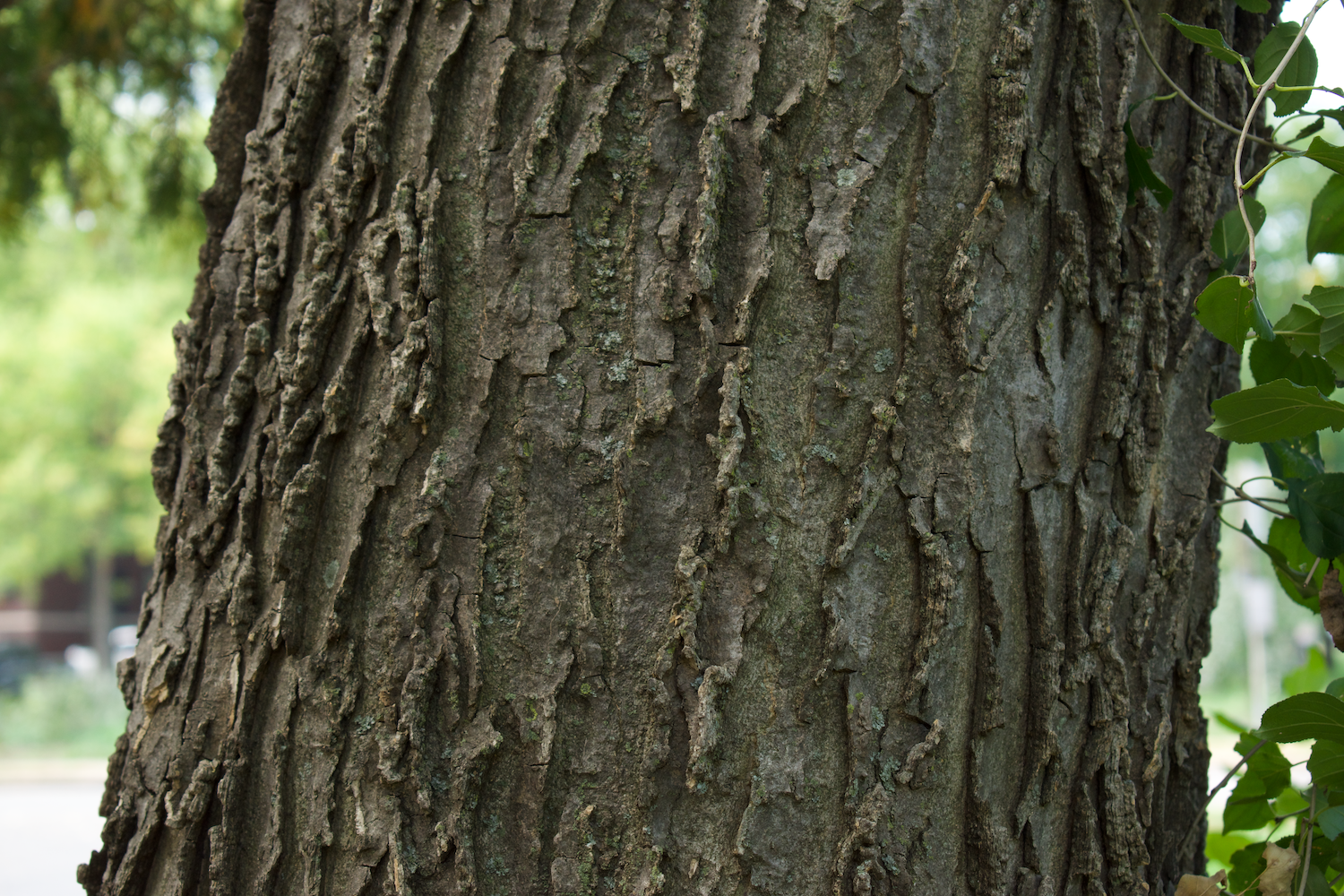

Though you may have some luck finding dead leaves around the base of the tree, I think that the best way to identify hackberry in the winter is by the bark! Hackberry has a rather peculiar bark that is grey in color and has corky ridges. Above are some examples of bark from different individuals. I like to say that it almost looks like someone “hacked” up the bark with a hatchet, which helps you remember that this tree is hackberry!

Juneberry (Amelanchier spp.)

A fruiting juneberry tree.

This small native tree may seem like an odd inclusion in a winter plant ID list, as its berries ripen in early summer. However, its distinctive growth pattern and bark make it fairly easy to learn to recognize, even without leaves, flowers, or berries to help you out!

Juneberries are also called shadbush, serviceberries, and Saskatoon berries. They are all shrubs or small trees in the genus Amelanchier, and various species grow across the US and Canada. It can be difficult to distinguish the species from each other, especially since hybridization between species is common. Thankfully, we only need to identify it to the genus for edibility purposes. (Though if you’re a plant nerd, you may want to work on getting familiar with the species, too!)

The bark of juneberry is usually smooth or mostly smooth, grey in color, and has vertical striations or fissures. When growing in a forest, juneberries can become rather tall (up to about 50 feet, depending on the species) and develop a long, straight trunk. However, most juneberries I see are planted in parks, yards, and in front of businesses. I also tend to find them in open areas like along lakes or in shrubby fields. When growing in areas such as this, they don’t need a long, straight trunk to reach the light. Instead, they spread horizontally and typically don’t exceed heights of 15 feet or so. They often create wide, branching patterns reminiscent of antlers. Otherwise, smaller species can display a more shrub-like appearance, with many small branching trunks.

Juneberries are an excellent wild edible, with a taste and texture that is probably most comparable to blueberries, but truly all their own. It is certainly worth getting to know this plant a little better so that you can identify it during the winter months!

Will You be Going Out this Winter?

Well, I hope I gave you enough reasons to go outside this winter and start identifying plants! Spring will be here soon, and with it will come a whole new array of wild edibles. But let’s try not to let winter pass by without learning a new thing or two about our friendly plant neighbors!

Join Us on Patreon!

This blog post was chosen in a poll by Patreon members. Thank you for your support! You can read about a 6th bonus plant from this list by becoming a patron today.

If you like our foraging tutorials, please consider joining us on Patreon! It’s a simple way for you to help Four Season Foraging keep producing the informative content that you enjoy.